Creating Volumetric Lights and Shadows Through Ray Marching

Some pictures showing the volumetric lighting effect in action, an espace full of light, a directional spot light, and a far away light giving the aspect of a sun.

Maybe it’s just me, but I actually do believe the effect of volumetric light is something that people interested in computer graphics are curious about when they start implementing different kinds of global illumination algorithm. I think this goes back to our perception of light in our everyday life. Everyone has seen this “effect” before, where we sort of see a “cone” of light created by a source of light, maybe from something like a lighting pole.

And then, when you start implementing illumination algorithms you realize that the only thing that allows us to know there is light in scene (well, you know, besides the scene not being in full darkness or just colored through ambient light) are things like specular highlights, or the shadow cast by objects. But we don’t actually see those “light rays” we see in reality.

However, that’s not wrong, that’s actually 100% correct. The thing is, these scenes that we are creating, like the ones I created on my previous ray tracing post, are essentially scenes in a vacuum. Scenes in a space where there is nothing but our objects and our light source. What is missing is something that is present everywhere in the atmosphere, what we call participant media. In those cones of light we see in reality, we are not seeing actual light rays coming from the light and hitting the floor, what we are seeing is light being reflected by participant media in the atmosphere, those are particles such as haze, fog, dust or smoke that are present pretty much every where. And if you want to render scenes with that effect, what you have to do is simulate the presence of those particles in the scene, so that’s what I did.

Ray Marching and Ray Tracing Hybrid

My idea then was to essentially “add” ray marching to my ray tracer engine, and actually use both techniques at the same time. The process begins by first using the Ray Tracing technique to check for intersections between the ray and the objects in the scene. If the ray does intersect with objects, the closest intersection point is saved, otherwise this process won’t affect the ray sampling.

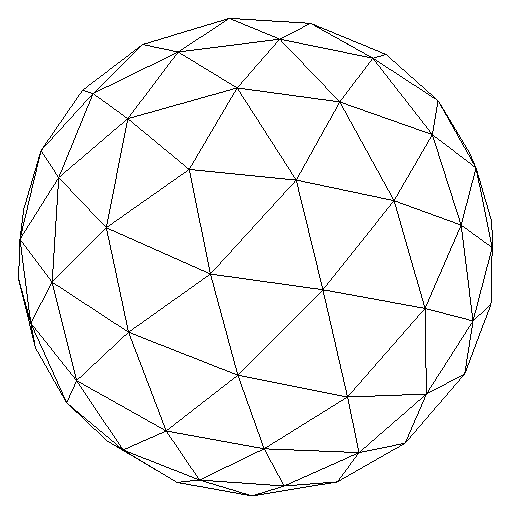

Diagram describing the Ray Marching process.

Next it’s necessary to start sampling the ray. The first thing required for this process is to decide when to stop, so that the sampling of the ray doesn’t go on forever. A scalar value is decided and that value is multiplied by the normalized ray direction to get the last sampled point. For instance, if a ray has a direction described by the xyz vector (0,0,1) and the user decides on a value of 10, the last sampled point will be (0,0,10). To choose this value we also need to take into account the objects in the scene, because the value should be such that it enables the ray to sample points further than the objects (otherwise some objects will not be rendered).

Now, given the origin of the ray (the camera/eye position) and this last sampled point, the user decides on the number of appropriate samples. The current implementation uses uniform sampling through the extremes. In other words, given the origin of the ray, the last sampled point and a number δ of samples, between the origin and the last point the process will generated δ points that are equidistant from each other (as seen on the figure above where the points are at a distance d from each other). In the case the ray doesn’t intersect any object, the result will be the exact number δ of points. In the case there was an intersection, as soon as a sampled point is farther from the origin than the intersection, this process stops and we will use only the sampled points behind the intersection, plus the intersection point.

Participant Media

The reason we do all this work with ray marching to get different points in the environment is because with those we can now simulate the presence of participant media in the atmosphere. To describe particles of some sort of participant media it’s necessary to have an absorption coefficient , a scattering coefficient and a phase function , which describes the angular distribution of light scattering at a point in the medium (Jarosz08).

And given the description of the particles and a point in our scene, we can calculate resulting intensity of light traveling through the atmosphere. This is calculated by the following equation (by Wyman08 and Hoffman03):

Where the first term corresponds to the attenuated light reflected from a surface and the second term represents the additional light contributed by in-scattering along the viewing ray. The first term of equation is calculated as

The second term can be calculated two different ways. That is because one way will describe an atmosphere with variable density of particles, while the other describes one with constant density. Those are:

I’ll leave the explanation of what all exactly all of those equations are doing and what those variables mean to your pleasure reading of the references. :)

Now, suffices to say that with all those variables in place, and with our samples points in the scene, we are able to simulate this columetric light and shadow effect. The algorithm we end up with is not really that complicated:

Show Me the Cool Pictures Already !!

Ok, ok. Now that all the math is done with we can finally play around with the engine and build some scenes. The design of the engine allows me do easily create these kind of scenes by simple “adding” some sort of particle in the world. It’s as easy as:

// create world, add objects in it

World world;

world.addObject(&greenSphere);

world.addObject(&blueSphere);

world.addObject(&thirdSphere);

world.addObject(&checkerFloor);

// add light and set up phong

world.addLight(&light);

world.setUpPhongIllumination( Color(0.25,0.61,1.00) );

// We are doing ray marching, se need to add values for participant media

world.addParticipantMedia(0.01,0.01,VARIABLE_DENSITY); // Ka and Ks values, plus the type of density

...

Camera cam(pos, lookAt, up, imageHeight, imageWidth, viewPlaneHeigth, viewPlaneWidth,

RAY_MARCHING, 50, RAY_GRID);

// render our world, get the color map we will put on canvas

std::vector<Color> colorMap = cam.render(world);Then when the world is rendered it will check if participant media was added, if it was it will proceed to sample the scene and calculate the necessary values. In this example code you will also notice a value 50 being passed when creating a Camera object. That value is the number of samples we will be getting from the camera to the scene limit. It’s a very important value, and you will see why in the following pictures.

Constant vs Variable Density

Here we see the result of running the algorithm for both a constant and variable density atmosphere in a scene with only light sources and no objects. Both scene are exactly the same with the exception of the type of atmosphere. We can see how a constant density scene shows barely any difference in lighting when far from the light position, meanwhile the variable atmosphere shows a clear difference, plus the effect of creating a sphere of light around the light position.

Sampling the Rays

Now, let’s check out some pictures with actual objects to see the effect of volumetric shadow and the importance of the number of samples.

With the objects we can easily see how a “cone” of shadow is created in the scene by the objects. That’s the effect we get by sampling the ray and trying to shoot shadow rays from those samples, the sampled points that are along the ray that hit the object and not the light are the ones that will be considred inside the shadow volume, and thus be rendered as black.

The pictures on the right show how the scene looks like with a relatively small number of samples, 50 samples. We can see that actually the light is not really affected that much by that, that’s because all of the sampled points will hit the light, so here it really doesn’t matter that much how many samples we will use. The real importance of the samples comes into play in the shadows. We can see how the shadows do not look right, it’s almost like we see sections of the shadow. That comes from the small number of samples, the rays that are right below the spheres would show “more shadow” because most of the sampled points hit the object, while rays on the “edge” of the object have only a few sampled points hitting the object. Obviously for a more realistic scene, we need more samples.

Playing around

Alright, with everything in place we caw now just play around with these settings to create some cool scenes. One of the things I decided to do from the start was to create a spot light, to have this cone of light shining down on some objects. This is not really that much complicated, given that you have a good design in your engine, because all you need beside the point of the light is a normal (the direction of the spotlight) and an angle (describes the volume of the cone). Then you just need to check if a shadow ray is “inside” the cone and then see if it hits the source.

And after I saw how the variable density created this cool sun-like effect close to the light another scene that came to my mind that I wanted to create was the one shown in the intro of 2001: Space Odyssey where you see the moon, earth and the sun in the distance. This one could for sure look even better with the right textures, but I’ll leave that for another time. :)

References

- Wojciech Jarosz. Efficient Monte Carlo Methods for Light Transport in Scattering Media. PhD thesis, UC San Diego, September 2008.

- C. Wyman and S. Ramsey. Interactive volumetric shadows in participating media with single-scattering. In Interactive Ray Tracing, 2008. RT 2008. IEEE Symposium on, pages 87–92, Aug 2008.

- Naty Hoffman and Arcot J. Preetham. Graphics programming methods. chapter Real-time Light-atmosphere Interactions for Outdoor Scenes, pages 337–352. Charles River Media, Inc., Rockland, MA, USA, 2003.