Implementing a Ray Tracer

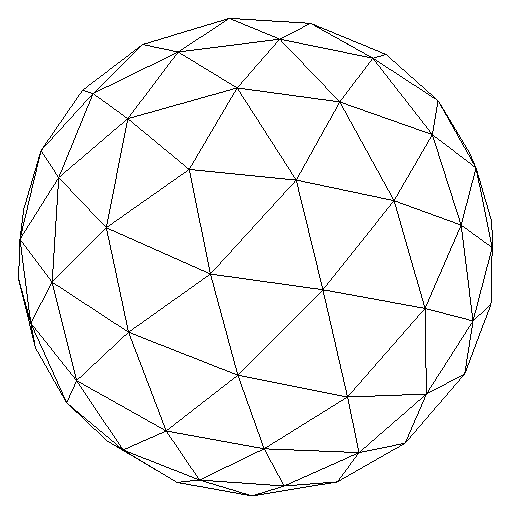

Here are few pictures rendered by my engine, some spheres with different illumination and reflection values, the recreation of the original picture rendered in Turner Whitted's ray tracing article, and the full Stanford Bunny (click on the pictures for full size).

I have been working on this implementation of a ray tracer for a long time now. Not only because implementing ray tracer by itself is already a considerably big endeavor, but also because adding some extra features to it takes a lot of studying, designing and testing those features adds a whole new layer of work on top of it.

I decided to implement a good old Whitted Ray Tracer, based a lot on the original paper (Reference), but also adding some new options on it. Here I’m not going to talk in length about what is a ray tracer and how it works, there is plenty of literature out there to help you with (and this really cool video from Disney Research too ). Instead I’m going to focus on a few features that I added and about a lot of small details you learn along the way of designing and implementing this project.

Make it fast

Ray tracing is a technique for rendering scenes that is considerably expensive. Shooting rays from the camera that will bounce around the scene takes up a lot of processing, and if you add to that anti-aliasing, lots of objects that transmit and reflect light, lots of complex geometry, area lights and all that good stuff, it will make the whole processing even more taxing. So doing the possible to make this whole process faster is crucial.

Multi Threads

I believe this is the first thing that comes to mind. Ok, so we are going to render a scene with a certain resolution, we will have at least one ray being shot from each pixel. And in this case, the result of one pixel does not depend on the result of the others, so really, there is no reason not to make this whole process concurrent.

So I did some research on what would be the best way to go about this using C++, because turns out there are a lot of ways to implement threads on this language. I ran into this really good article by Intel going over the options, but in the end the best option for me was using C++11 threads. This was actually one of the few times I ever used features from C++11, and what helped me a lot was in fact this great step by step article by Foster Brereton.

Adding multi thread support for the ray tracer was as easy as adding the following code. The idea is simple, we get the number of cores the computer has, and each one will be responsible for each pixel (and if we have more than one ray per pixel, each core will shoot all these rays).

int cores = std::thread::hardware_concurrency();

volatile std::atomic<int> count(0);

std::vector<std::future<void> > futureVector;

// Result color of a ray

std::vector<Color> colorMap(pixelNum);

while (cores--) {

futureVector.push_back(

std::async([=, &colorMap, &world, &count]()

{

while (true) {

int index = count++;

if (index >= pixelNum)

break;

int i = index / imageWidth;

int j = index % imageWidth;

colorMap[index] = getColorInPixel(world,i,j);

}

}));

}Some people might be wondering about another approach, which is get a pixel and shoot n rays from it, and have each of those rays be calculated by different threads. I also thought about this approach (and implemented it in fact), however in this case we run into the problem of having to wait. Because although one pixel does not depend on the other, when we are in the same pixel the final result depend on all the rays. So, from the n rays we shot in this pixel one finished first? Too bad, you have to wait for the other n-1 rays to finish so we can have the final color value of this pixel and then keep going. So, yeah, not a really good approach.

3D Data Structures

Now, the thing that really makes the whole process much faster is adding a 3D data structure. Ray tracer is probably really intuitive if you are a programmer, but 3D data structures have a specific field in which they are used, so there are people who probably never dealt with then.

For my ray tracer I implemented a good old Kd-Tree. How this thing works, you can look that up because there are plenty of resources out there, but essentially it divides our three dimensional space into voxels with objects inside of it. The idea is the ray will travel through those voxels, so we will have all of the space mapped and we know beforehand which voxels have which objects, in other words, we know when each ray should check if it intersects with which objects. This makes the whole process dramatically faster, although it’s implementation is not trivial, it involves creating the Kd-Tree given the objects, checking if an object (or part of it) is inside the pixel, and of course the logic of rays traveling through these voxels. The payout, however, is great as you will see in the table further below.

The Right Compiler Tuning

This is a detail that I believe most people gloss over, but is actually really important. Most of us have probably heard about how compilers are really smart and they in fact make your code faster. This is 100% correct, however, there is some fine tuning you can do on compilers to make it even better.

By implementing all of this in C++ the compiler I am using, and I believe most people probably do, is the unix based g++. This is a compiler tested through time, with lot of interesting options you can use. The flags that can help us here are:

-march=native: This flag will activate a number of different flags based on the architecture of your computer.

-03: This flag will try to optimize the code at the expense of compile time and the ability to debug the code.You can read more about this at gcc’s online manual. There might be more flags that could make things faster, or maybe reasons for why you should/shouldn’t use on the them. Regardless, in my current environment the use of those flags did help with the overall processing time of rendering a scene.

Results

So here are a few results regarding rendering time. I made a relatively simple picture to test the different options, because if it was too complex the single threaded with no kd-tree would take a ridiculous amount of time, but still with some interesting geometry. What we have here is a 1024x1024 resolution picture with 8 rays per pixel, and no bouncing objects. It’s a picture with a rectangle light (with 9 samples on a 3 by 3 grid), a floor and a wall, and the stanford bunny with the least amount of triangles (the “bun_zipper_res4.ply” file you can get on Stanford’s website). It’s essentially the same scene as the one I’m using on the header of this post, but with a less features.

On the left we have the scene used for the time results on the table below. It's slightly different from the right scene, which has the complete stanford bunny, more rays per pixel, more sampling on the light, etc.

| Rendering Features | real | user | sys |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single thread, No Kd-Tree | 60m21.832s | 58m35.507s | 0m23.571s |

| Single thread, With Kd-Tree | 24m53.260s | 24m8.510s | 0m9.416s |

| Multithread, No Kd-Tree | 18m42.697s | 65m49.113s | 0m15.442s |

| Multithread, with Kd-Tree | 10m44.172s | 42m4.177s | 0m1.469s |

Timetable to render the left image.

So we pretty much get the expected result, the simple single threaded process is much slower than the one using a Kd-Tree and multithreads. Also, here is a protip I learned while implementing the Kd-Tree: don’t forget to use it in all of your spawned rays. In my first implementation of it I was actually only using it on rays shot from the camera to the scene, and I had forgot to use it when rays hit a surface and a shadow ray was shot. In other words, all the shadow rays ended up having to check all the objects for intersections to see if it hit the light or not, instead of traversing through the tree. At first I did not even notice this was an issue, because even in this case you can render the scene faster. However, when I tried in a complex scene, such as the complete stanford bunny with area lights, I noticed it was taking way too long. And that’s when I noticed the problem.

But anyways, looking at the render times, not really that hard to see that Kd-Trees and multithreads make our life much easier. From one hour to 10 minutes? That’s pretty good. Also, to keep things in perspective, I was running all this on an early 2015 13’ Macbook Pro with a 2.9 GHz (i5-5287U) dual-core Intel Core i5 Broadwell.

Make it bright

Well, obviously with a ray tracer the whole thing is global illumination, BRDFs and all that fun stuff. Otherwise, we couldn’t really see anything, could we? In my ray tracer I have implemented both Phong and Phong-Blinn. These are relatively easy to implement, just a matter of how you deal with view vectors. But the thing that gives us a more realistic scene are area lights.

With the architecture of my engine, it was relatively easy to create area lights. The idea is to make a light “object”, that has an actual object (like a rectangle and a sphere) attached to it. Then, differently from a point light, when a shadow ray is cast and tries to reach the light it will need to try to reach a number of points sampled from the area light.

This creates a much more realistic scene because of how the light affects the objects, and because of how shadows end up being created. Since there are some points where only a few of the shadow rays reach the light, and some don’t, we end up with the effect of umbra and penumbra. The issue is that it makes the whole scene more expensive. This is because, not only you need a decent number of samples on the light surface, but also because you need a high number of rays for anti aliansing, otherwise the scene ends up looking like it has a bunch of noise on it.

Make it textured

And to be able to create more interesting scenes it’s also possible to add texture mapping in our objects. Texture mapping given a texture picture is done the normal route, create U and V coordinates for texture and then map it on the surface. The more interesting kind of texture you can also do in this engine is procedural textures. That’s the checkered floor you can see in the original ray tracer paper. It can range from really complicated to pretty easy. There is support to add any number of different textures on the engine, but I focused on recreating the texture floor, and to adding textures to spherical objects, as you can see below.

On the left we have the classic whitted ray tracer scene with a procedural checkered texture on the floor, and on the right we have spherical texture mapping on some spheres.

The problem with direct light

In the end I was able to implement a really robust engine that enables me to create a lot of different scenes with different characteristics. The only “issue” is that a Whitted Ray Tracer is mostly interested in the effects of direct lights. Which means, when you render a scene shooting rays from the camera and trying to hit the light, you actually miss some of the the contribution light can have to the overall scene. This can be easily seen in scenes where light is shining though some sort of hole in a room, for instance the famous Cornell Box seen below.

As you can see when considering only the direct light we have a problem where the contribution of light that is bouncing around is not seen in every object, most notably the ceiling. This effect, although not realistic, is correct considering how direct light works: light from the camera hits the ceiling, the tries to hit the light and it can’t. You might even try to make the ray bound from the ceiling, but then what you get is really just reflections from the floor.

The next step to be able to create this kind of scene is implementing a bidirectinal ray tracer, that considers both direct and indirect light. You guys gonna have to wait for another post about that, because this feature is still a work on progress right now. ;)

References

- Intel Developer Zone - Intel Developer Zeno: Choosing the right threading framework

- Multi Threading in Ray Tracing - Foster Brereton article on adding multithreads on ray tracing.

- GCC Manual - GCC Manual.